Few poets have attracted as much interest and scholarship as John Keats, one of the most beloved of the romantic poets. Both his life, tragically curtailed in 1821 at the age of 25, and his work continue to be analysed and discussed. While much is known about his final prolific four years, uncertainties about his life during the preceding seven years continue to prompt debate. Yet his ‘medical’ years, from the age of 14 to 21, had a profound effect on his poetry.1 This paucity of documented facts has inevitably led to a variety of accounts.

One incontrovertible event in 1817, however, provides a potential key to unlocking the likely narrative: his selection, from scores of aspiring surgeons, to be appointed to a dresser-ship at Guy’s Hospital.2 Given he’d been registered as a pupil for less than a month, the reason for his selection could reveal much of the mystery of Keats’ life from 1810 when he started his apprenticeship to Thomas Hammond, an apothecary-surgeon, in Edmonton, nine miles north of London.

Wilston House, Edmonton. Home to Thomas Hammond, John Keats’ master 1810–1812

Before considering the events in Guy’s Hospital, an understanding of how hospitals were staffed and the professional and hospital politics in 1817 is needed.

Hospital staffing in 1817

As in the six other large public hospitals in London, Guy’s had three senior surgeons who provided their services for free, though benefitted substantially from pupils’ and dressers’ fees.3 In addition, the cachet of such an appointment boosted their appeal to their fee-paying private clientele, their principal source of income.

Entrance to Guy’s Hospital

To qualify to become either a licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA) or a member of the Royal College of Surgeons (MRCS), candidates had to have completed five years as an apprentice to a surgeon or apothecary-surgeon (general practitioner). In addition, six months attendance at a hospital was required for the LSA and twelve months for MRCS.

While becoming a pupil depended on being able to afford the registration fee (24 guineas for 12 months), the alternative of becoming a dresser not only cost twice as much (50 guineas, equivalent to £5000 today) but also required selection by the senior surgeons.4 Dresser-ships were much sought after and essential if someone had ambitions to become a hospital surgeon (rather than a general practitioner). The basis of selections is unclear but probably depended on who you knew rather than on merit and skill.

Each of the three surgeons had four dressers whose main roles (in addition to studying for their exam) were to assist at operations, dress wounds after surgery (in theatre and on the wards), see and treat emergency patients and support the surgeons on their twice weekly ward rounds.5 At Guy’s, with twelve dressers, the rota demanded a dresser lived in the hospital for one week in twelve.6

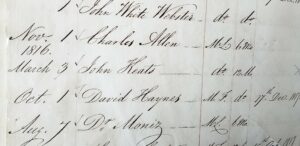

John Keats’ registration as dresser 3 March 1816 (King’s College London Archives G/FP/3/2).

Guy’s Hospital surgeons

In March 1816, the three surgeons were Thompson Forster (appointed 1790), William ‘Billy’ Lucas (1799) and Sir Astley Cooper (1799). Lucas had succeeded his father and Cooper, his uncle. Usually dressers (four for each surgeon) were appointed each autumn for twelve months.7 Cooper only appointed dressers from his own apprentices who had paid the handsome price of £500 for their five to seven year attachment to him. This compared with around £200 for an apprenticeship with an apothecary-surgeon. Fees covered board and lodging and tuition, with the quality of both varying enormously between masters.

Why was Keats appointed as a dresser?

On what basis was Keats offered a dresser-ship after only being formally registered as a pupil for three weeks?

One of the earliest suggestions, which appears in the highly respected biography by Robert Gittings was Keats’ resemblance “in name and physical appearance” to a famous contemporary surgeon.8 Intriguingly, who that surgeon might have been has never been revealed and this remains a colourful but fanciful suggestion.

John Keats (William Hilton, 1822)

Second, there is a suggestion that it was George Cooper (no relation), one of Astley Cooper’s dressers at the time, who recommended Keats. This is based on the fact that from March 1815 (six months before registering as a pupil) Keats had shared lodgings at 28 St Thomas Street with him and Frederick Tyrell, one of Astley Cooper’s apprentices. It has been postulated that George Cooper recommended Keats as early as November 1815,9 only one month after registering as a pupil, and that Keats was promised the next available vacancy, though there is no documented evidence of this having happened and unlikely that the opinion of a dresser would hold much sway.

A third idea appeared in Andrew Motion’s biography.9 Described as “the usual explanation”, it was simply that Keats had such a “vivid physical presence”. While he probably did stand out – he was only five feet tall, waif like with long flowing locks and, unlike other pupils, dressed in Byronic style – it hardly seems sufficient basis for appointing a dresser. Indeed, it might have been seen to be disadvantage.

Motion puts greater store in another explanation. Edmonton, where Keats had been an apprentice, was about nine miles north of the Borough hospitals. Three miles further on lay Enfield where John Abernethy, a leading surgeon at Barts Hospital spent weekends and holidays. He is said to have dominated the social life of the local community. The suggestion is that Keats’ master, Hammond, was part of Abernethy’s circle and would have spoken to Abernethy of his apprentice. In turn, Abernethy would have passed on any recommendation to his friend/acquaintance at Guy’s hospital, Astley Cooper, who in turn would have influenced his colleague Lucas. Apart from depending on several assumptions, this conflicts with the reports from several observers that the relationship between Hammond and Keats was strained at best and adversarial at worst. So much so, Hammond terminated the apprenticeship early. Hardly grounds for a recommendation unless Hammond was motivated by feeling responsible for letting Keats down.

The fifth explanation is predicated on the notion that it was actually Astley Cooper who determined appointments to all the dresser-ships at Guy’s, not just his own. In his excellent biography of Cooper, Druin Burch proposes that even before Keats became a pupil, Cooper was aware and impressed by Keats’ character.10 The evidence often cited for this is that it was Cooper who, in March 1815, offered Keats the opportunity to share lodgings with one of his dressers and apprentices with the express desire they looked after him. (There is even the suggestion that this happened a year earlier, in 1814, but that seems unlikely.11)

This then raises the question, how would Cooper have formed such a strong opinion of Keats, months before he registered as a pupil? It would either have been through a recommendation from Hammond or from personal observation. The former is unlikely given Keats’ frosty relationship with Hammond and the lack of any documented link between Hammond and Cooper (though it is possible they had met in 1786-7 when Hammond was a dresser at Guy’s and Cooper was assisting Cline with dissection at St Thomas’s).’

The latter, personal observation, is only feasible if Keats had been frequenting Guy’s and attending Cooper’s lectures and ward rounds before he was formally a pupil in October 1815. In the most recent biography of Keats, Nicholas Roe describes how some apprentices (presumably those living locally) obtained tickets of admission to attend lectures before completing their five years.11 It is feasible for Keats to have attended Cooper’s lectures in the first few months of 1815, thus enabling the surgeon to gain a favourable impression of his capabilities.12

The sixth and final factor to consider is nepotism. Thomas Hammond had himself been dresser to Billy Lucas’s father, William Lucas Sr. as had John Hammond, his brother. Despite his poor relationship with Keats, it’s conceivable that Thomas Hammond recommended Keats to Billy Lucas, reminding him of the earlier family associations. The power of such connections in medical appointments was strong and may well have played a part. There were also additional familial links – Thomas Hammond’s niece had married Joseph Green, dresser to a surgeon at St Thomas’s Hospital – though that is a rather distant connection.13

A plausible scenario

Despite none of these putative explanations by themselves proving entirely convincing (as their proponents are the first to point out), all but the first could have contributed. Drawing on knowledge of the ways the profession and hospitals were organised and governed at the time, a plausible scenario that incorporates elements of all five explanations can be constructed.

1810-1812 Apprenticeship with Hammond

In August 1810, at the age of 14, John Keats commenced his five-year apprenticeship with local apothecary-surgeon, Thomas Hammond of Edmonton. The price was about £200, using up much of his inheritance from his recently deceased mother. His desire to be a doctor was tested by the life an apprentice led. Like Hammond’s previous apprentices, Keats wasn’t housed in his master’s large, comfortable home (Wilston House) and made to feel a member of the family but in rooms above the surgery in a small building in the grounds.

Keats resented the drudgery of the chores he was given, treated more like a servant than a trainee. It was a wretched life. He felt humiliated when made to stand in the street outside his old school in Enfield, like a stable-boy, holding Hammonds’ horse and carriage while his master visited a patient. Neither Keats nor Hammond were easy-going. Keats was said to be ‘fiery and forthright’ and have a volatile temper. After only two years, an incident occurred in which Keats raised a “clenched hand against Hammond”.

1813-1815 Poetry and medical lectures

In 1813, Hammond terminated the arrangement. He surrendered the indenture to Keats, the document that provided evidence of Keats having undertaken a five-year apprenticeship, but none of his original £200 payment was returned. Needing somewhere to live, Keats joined his younger brother, Tom, in his lodgings nearby.

Keats made good use of his freedom over the next two years living in Edmonton. Influenced and encouraged by his old English teacher, Charles Cowden Clarke, he commenced writing poetry. He now had time for weekly visits to Enfield to spend time with Clarke.

Meanwhile, he pursued his medical ambitions by attending lectures at the Borough hospitals. It was possible to obtain tickets of admission without being a registered pupil, though lax security and huge audiences would have made it easy to attend unaccosted anyway.

Among the lecture courses he attended during the winter of 1814/15 were those of Astley Cooper, held two evenings a week from the start of January. It seems unlikely that Keats would travel back to Edmonton late in the evenings in mid-winter so must have stayed somewhere in Borough. A bed in one of the many inns would not have cost much.

Unlike most lecturers, Astley Cooper would loiter in the theatre at the end of the session, encouraging inquiring pupils to flock about and assail him with questions. If Keats was one of them, he could have made a favourable impression on Cooper. This is where Keats unique appearance might have played a part, marking him out and attracting Cooper’s attention. That and the nature of his insightful questions, for he was clearly intellectually bright and able. If, in addition, Keats barely concealed his developing radical views, Cooper might well have warmed to him even more given he himself, at heart, was a radical (it had even been suggested he had been a Jacobin).

John Keats. Life-size bronze, Guy’s Hospital (Stuart Williamson, 2007).

1815-1816 Pupil at 28 St Thomas Street

By March 1815, Astley Cooper must have discovered Keats circumstances. The only obvious source would have been Keats himself. Cooper would have known Keats couldn’t register to be a pupil until the end date on his indenture document, October 1815. Learning that Keats had to commute from Edmonton and knowing that one of his dressers, George Cooper, and an apprentice, Frederick Tyrell were in need of a third tenant to share the cost of their lodgings in St Thomas Street, Astley Cooper suggested Keats move in with them. Cooper’s interest in Keats must have been considerable given that he was keen to place him under the guidance of his dresser and apprentice.

Drawing on his remaining bequest, Keats took up the offer. He could now spend much more of his time in the hospitals, watching operations, attending lectures (though courses and dissection finished by June), and going on ward rounds (while still leaving time for poetry and occasional visits to Clarke in Enfield.) George Cooper enabled him to help in Astley Cooper’s small dissection room in St Thomas’s. In this way, Keats education accelerated such that by October he had completed half his studies before formally registering as a pupil.

His diligence, obvious intellectual ability and enthusiasm meant that when, that autumn, Billy Lucas sought to identify a new dresser for March 1816, George Cooper could recommend Keats. When Lucas then discovered that Keats’ master, Thomas Hammond, had been his father’s dresser, the die was cast. Whether or not he ever learnt about or was bothered by Keats falling out with Hammond and his apprenticeship being terminated early is unknown.

Misfortune and fortune combined

Keats appointment as dresser can be seen to be not so incredulous or mysterious as it has seemed. A mixture of misfortune – a troubled and frustrating apprenticeship, terminated early – and good fortune – earning Astley Cooper’s patronage – combined to pave the way for his appointment. Although Astley Cooper never appears to have documented his views of Keats (nor vice versa), it’s possible that Cooper saw his own suppressed radicalism reflected in the pupil, valued it and sought to nurture it. If so, Astley Cooper’s contribution to Keats’ life might be greater than previously recognised.

References

- Roe N. The art of medicine. John Keats, medicine and poetry. Lancet 2021;397:962-3

- Guy’s Hospital. Entry of Physicians, Surgeons Pupils and Dressers pre-1814 (G//FP3/1) and 1814-1827 (G/FP3/2). King’s College, London Archives

- Ghosh H. John Keats’ Medical Notebook: Text, Context, and Poems. Liverpool University Press, 2022

- Anonymous. The Hospital Pupil’s Guide through London. 1800

- Golding B. An historical account of St Thomas’s Hospital, Southwark. London, 1819

- Wilks S, Bettany GT. A biographical history of Guy’s Hospital. Ward, Lock, Bowden & Co., London, 1892

- Barnard, J. ‘The Busy Time’: Keats’s duties at Guy’s Hospital from autumn 1816 to March 1817. Romanticism 2007;13(3):199-218

- Gittings R. John Keats. Heinemann, London, 1968

- Motion A. Keats. Faber & Faber, London, 1997

- Burch D. Digging up the dead. Vintage Books, London, 2008

- Roe N. John Keats. A new life. Yale University Press, New Haven, 2013

- Feltoe CL. Memorials of John Flint South. London 1884

- Burnby JGL. The Hammonds of Edmonton. Edmonton Hundred Historical Society, Occasional Paper No 26. 1973

Published in Journal of Royal Society of Medicine 2024 https://url.uk.m.mimecastprotect.com/s/RkphCB6q0U60gr7u6hkC26Ng-?domain=doi.org