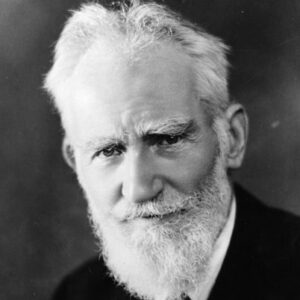

Concerns about doctors and medical practice that so exercised George Bernard Shaw in 1906 when his play, The Doctor’s Dilemma, was first produced are still relevant today: rationing, moralising, ineffective treatments, misguided financial incentives, lack of accountability.

In England, there are daily accounts of patients being denied hip or cataract surgery because of a lack of sufficient resources to treat everyone. Doctors’ decisions as to whether to treat someone or not may be influenced by whether a patient smokes or is overweight, considerations that are as much moral as medical. Disagreements within the medical profession about the usefulness of many treatments continue, disputes that can at times become heated, as seen when doctors at University College Hospital, London vehemently opposed the incorporation of the Royal London Homoeopathic Hospital in their Trust as they considered homoeopathy no more than mumbo-jumbo. And Shaw’s concerns about the undesirable influence of financial incentives still stalks the same streets of Marylebone. A modern example was advertisements for ‘cures’ for ‘Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder’, a supposed ailment created by some doctors (and a drug company) who went on to claim that almost half of all women were afflicted. The advertisements will have raised anxiety and, no doubt, persuaded some gullible people to part with their money. But Shaw’s greatest criticism was doctors’ lack of accountability. While changes have occurred, a doctor is still more likely to be struck off for a sexual indiscretion with a patient than for killing them.

While such features of medical practice unfortunately persist, it would be wrong to despair at any lack of progress over the past century. Unknown to Shaw, he was writing at the time of the birth of modern medicine. Until 1900, doctors had had little to offer in the way of effective remedies. But during the closing decades of the 19th century, key advances in understanding (such as evolution and germ theory), in the investigation and diagnosis of diseases (using new technologies such as X-rays, sphygmomanometers and electro-cardiograms) and in treatment (with safe anaesthesia and the use of aseptic surgery) were to transform health care. These were followed during the first half of the 20th century by the discovery and introduction of many effective drugs, most notably antibiotics.

While these developments were to dramatically transform people’s lives, their uncontrolled introduction by, at times, over-enthusiastic doctors, actually exacerbated some of the concerns about the medical profession that Shaw had eloquently described. For example, the obvious benefits to patients of safe anaesthesia was accompanied by surgeons’ freedom and enthusiasm to venture even more boldly into the body. While such increased experimentation was often to lead to improvements in what surgery could offer, such unregulated innovation was inevitably accompanied by failures, to the detriment of unfortunate patients. Another example in the early 20th century was enthusiasm about the supposed benefits of radiation as a panacea. Before its dangers were recognised, countless children had their tonsils irradiated for simple tonsillitis, a treatment that will have also exposed their thyroid glands and increased their risk of developing thyroid cancer later in life.

Biomedical science certainly led to significant improvements in medical care during the first half of the 20th century, thus reducing (though by no means eliminating) Shaw’s concern about ineffective treatments. However his other criticisms of the medical profession remained largely unaddressed in the UK until the 1950s. Although dubious financial incentives persisted in the private sector, for most people the establishment of a tax-funded public health care system in the UK in 1948, with salaried doctors in hospitals (though not in general practice), largely removed this hazard from specialist care. No longer did patients need worry that investigations and treatments recommended by doctors might be motivated by their pecuniary interests (though unnecessary procedures might still be carried out but not driven by financial gain).

But we had to wait until the 1980s to see Shaw’s other main concerns start to be addressed effectively. Since than we have seen an increasing acceptance by the profession of the need for rigorous scientific evidence as to the benefits of medicine. No doctor would now publicly argue against the need for ‘evidence based medicine’, even if debates continue about the adequacy and appropriateness of the available evidence. Such a development has been accompanied by the adoption of national clinical guidelines as to how doctors should treat particular conditions, produced and endorsed by the medical profession itself. Which is not to say that such guidelines are always enthusiastically welcomed and adhered to by doctors.

Meanwhile successive governments have sought greater accountability of the profession by requiring the doctors’ regulator, the General Medical Council, to have a majority of lay members on its council (something Shaw advocated) and, later this year, a system for checking on all doctor’s competencies every five years (revalidation) will commence. Having seen, in recent years, the cardiac surgeons provide the public with information on the outcomes of their operations, the government is now requiring other doctors and hospitals to disclose their outcomes. Shaw’s dream of accountability is starting to be realised.

Much of this progress could not have been achieved without the support and efforts of doctors themselves, many of whom welcome rather than resist greater openness with their patients. But not all. The language of Shaw’s doctors may have changed but the range of views expressed by them can still be heard today. But despite some doctors bemoaning the loss of a bygone arcadia in which they enjoyed greater autonomy, the persistent buoyancy of applications for admission to medical schools suggest that Mrs Dubedat’s view remains intact: “What a glorious thing it must be to be a doctor!”

First appeared in July 2012 in the programme for the National Theatre’s production of The Doctor’s Dilemma.